Modality in music is special—‘special’ as in “distinct from non-musical senses of the term;” and ‘special’ as in “possessing a striking allure and freshness.”

Often enough, modality has also been confusing.

In this post, I’ll illustrate some basic points about the musical modes, focusing on a well-known Irish fiddle tune, Banish Misfortune, which exists in a couple of different modal variants.

Let’s start with the tune itself. I liked it so well that I decided to write a set of piano variations based upon it. Here’s a video of my setting—the ‘theme’ of the set of variations:

(To put in a shameless plug, you can buy the sheet music for my variations here. Click and scroll to the bottom of the page.)

Somewhat unusually, Banish Misfortune is a three-part tune (most traditional dance tunes have two parts.) Each part concludes with the same cadence figure—a melodic pattern that ends the phrase. (This is sometimes called “cadence rhyme.”) Here, it helps make very clear the three-part structure of the tune.

But as mentioned above, there is more than one version of this tune. That is not unusual in folk music; tunes are transmitted aurally, not primarily ‘fixed’ in written versions. Each player is free to add, simplify or vary the melody, and the result is that popular tunes can exist in numerous different versions. Banish Misfortune certainly fits that description.

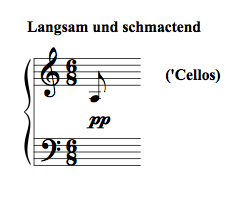

The first version to be written down dates from 1850, when Edward Cronin’s performance was transcribed and published in a famous compendium of Irish tunes. That version is shown together with the one I used, with the ‘1850’ version on the upper staff. The transparent blue enclosures highlight the ‘cadence rhyme,’ which is present in both versions. (There are four enclosures, not three as you might expect, because in the Cronin version the ‘B’ part of the tune has two different endings.)

If you look carefully at the second version–yes, I know it’s awfully small!–you might notice something: the C-sharps are found only at the cadences—outside the blue boxes, only C–naturals are to be seen. Not in the 1850 version, though: in it, one finds C-sharps consistently.

That note—C-sharp versus C-natural—is the difference defining the different modes of these variants of the tune. The 1850 version is in D major, whereas the later version is in the modal scale we would call D Mixolydian. From a scalar perspective, one note is all it takes!

Here is a table illustrating the point for the three ‘major-like’ modes:

| Name of Mode | Scale Degree Inflected |

| Mixolydian | 7th lowered |

| Ionian | None |

| Lydian | 4th raised |

The “Ionian” mode’s scale does not differ from that of major keys—though theorists might differentiate between Ionian and major on other, more subtle, grounds. Mixolydian features a lowered 7th scale degree, as just illustrated by the C-naturals of the second version of Banish Misfortune. Lydian is defined by a raised 4th scale degree—the Cronin version could be converted to Lydian, for instance, by raising all the G-naturals to G-sharp.

It’s a bit strange, isn’t it? (And I don’t mean the cut-off last line–sorry about that.) The characteristically Irish melodic turns and rhythms assort oddly with a mode that is not at all typical of the genre.

The three ‘minor-like’ modes, like their counterparts tabulated above, can be listed in reference to a central mode, from which the other two differ by a single altered scale degree:

| Name of Mode | Scale Degree Inflected |

| Dorian | 6th raised |

| Aeolian | None |

| Phrygian | 2nd lowered |

Aeolian corresponds to the so-called ‘natural minor scale.’ Dorian—like Mixolydian, a fairly common mode in Western European folk music—differs by a raised sixth scale degree (relative to the Aeolian.) (Readers familiar with the well-known tune “Greensleeves” may possess an example of this: that tune is heard in both Dorian and Aeolian incarnations.) Phrygian—more ‘exotic’ to many listeners—features a lowered second scale degree.

These six modes, by the way, complete the catalog of the ‘authentic’ modes in the scheme of Heinrich Glarean (June 1488 – 28 March 1563), an important figure in the history of modality (and of music theory generally.) Here’s Holbein’s sketch of “Glareanus”:

Click here to read more about him.

Click here to read more about him.

There’s another way to look at the modes, though: one can envision them as rotations of a single set of tones. To put it another way, imagine the white keys on a piano, which give the notes A through G. Of those seven notes, one can then form seven distinct scales, simply by taking each note in turn as a central tone, or ‘final.’ Here’s a table illustrating this way of thinking about the modes:

| Name of Mode | Final (“Starting tone”) and scale degree, relative to the major (Ionian) mode. |

| Locrian (not used, traditionally) | B (7th) |

| Aeolian (Natural Minor) | A (6th) |

| Mixolydian | G (5th) |

| Lydian | F (4th) |

| Phrygian | E (3rd) |

| Dorian | D (2nd) |

| Ionian (Major) | C (1st) |

In a way, that approach is illustrated by the notation chosen above for the dual versions of Banish Misfortune. Some astute (and detail-oriented!) readers may have noticed that although the tune is in D, I used the key signature appropriate to G major.

That is quite normal for the Mixolydian version of the tune (lower staff.) Consider it from the perspective of G major. If G is ‘scale degree 1,’ then ‘scale degree 5’ would be D. And, according to the table above, it is ‘scale degree 5’ which forms the final of the Mixolydian scale.

Thus, D Mixolydian would usually be written with a key signature of one sharp.

Let’s turn back to the tunes themselves for a bit. A quick overview can be had by listening to the two played simultaneously. It’s not a particularly pleasant musical experience, it must be admitted—the modal clash between C and C# does sound quite sour —but the simultaneous presentation does rapidly highlight where and how the tunes diverge or coincide.

You can tell that the first section differs the most, while the second section is most similar—in fact, for much of the second section it sounds as if just one tune is playing. The third section occupies an intermediate place in this scheme.

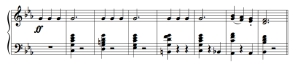

I’ve illustrated that visually below. The green boxes highlight specific similarities of pitch or contour; the yellow-orange boxes identify a more subtle correspondence found between the ‘A’ sections of the tunes: for six successive downbeats, the two melodies form a dyad—a pair of pitches—from the tonic triad.

I hesitate to make too much of that relationship, but it does suggest a static tonic ‘harmony’ underlying this section of both melodies. (Traditional performances would likely have been unaccompanied.) The same cannot be said of harmonies of the other two sections of the tune, which seem to imply non-tonic harmonies. (The 1850 version actually states a dominant (A major) triad by arpeggiating it in measure 20.)

There’s an irony here: a modern listener might tend to perceive the modal version of the tune as more ‘primal,’ older, while the 1850 version seems somewhat conventional. The reality is different: though I don’t know when the earliest Mixolydian version of Banish Misfortune dates from, it is said that the popularity of versions such as the one I used (and present above) dates only from the 1960s, when the renowned Irish band The Chieftains recorded it!